FreelingWaters

Cabinets

ISBN 9789464770858

design and editing: Jurgen Maelfeyt

text: Emmet Byrne (Walker Art Center Minneapolis)

April 2025

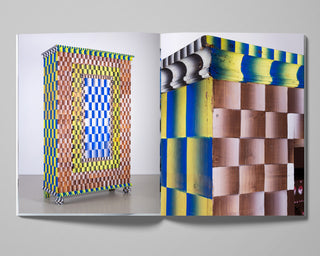

How satisfying it must be to arrive upon an idea that is large and rich enough to sustain years of experimentation. Painter Gijs Frieling and typographer Job Wouters have been lucky enough to find one. Known collectively as FreelingWaters, they have applied their imagery to a variety of surfaces, from walls and buildings to billboards, books, clothing, and even coffins. For their new project they have turned to antique cabinets, which they see as all accommodating vessels just begging to be invested by the imagination. But instead of cabinets filled with curiosities, FreelingWaters’s cabinets are themselves the curiosity.

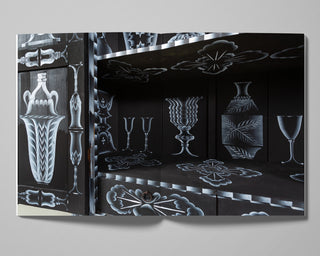

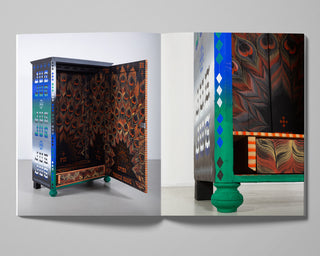

Building upon a history of northern European painted-pine cabinets, Frieling, whose imagery is inspired by 18th-century folk art and pre-Renaissance wall painting, and Wouters, a specialist in typography and calligraphy, turn traditional ornamentation into a psychedelic wonderland. Through repetition and vibration, intricate patterns become joyful optical noise that suggests contemporary reference points: television static and cathode-ray tube glitch art, magic eye illusions, Rorschach tests, and even fractals. When researching traditional painted cabinets, the artists came across a phenomenon whereby some patterns (such as marble) were copied by successive artisans over the years to the point where, eventually, they lost all semblance of the original. This recursive game of telephone could be an apt description of FreelingWaters’s work in general, though their distortion is intentional instead of accretional — reference points reimagined and reworked over and over through the embodied practice of painting and conceptual curiosity, coming out the other end as something alien yet still recognizable.

Beautiful as these pieces are in galleries, restaurants, and offices, I’m drawn to how an individual might develop a relationship with such an object over time. How a child might experience the vivid colors, psychedelic patterns, and surreal imagery. How they would lie on the floor and reach up to rub the wood with their hand, or hide from their siblings inside them. (It was through a wardrobe, after all, that the Pevensie children found the land of Narnia.) As forms, these cabinets are filled with wonder and mystery. In them, Frieling and Wouters have also found a liminal space to house their ambitions, somewhere between dimensions, between decoration and figuration, between public and private, between past and future. Who wouldn’t want to live with such impossible objects?